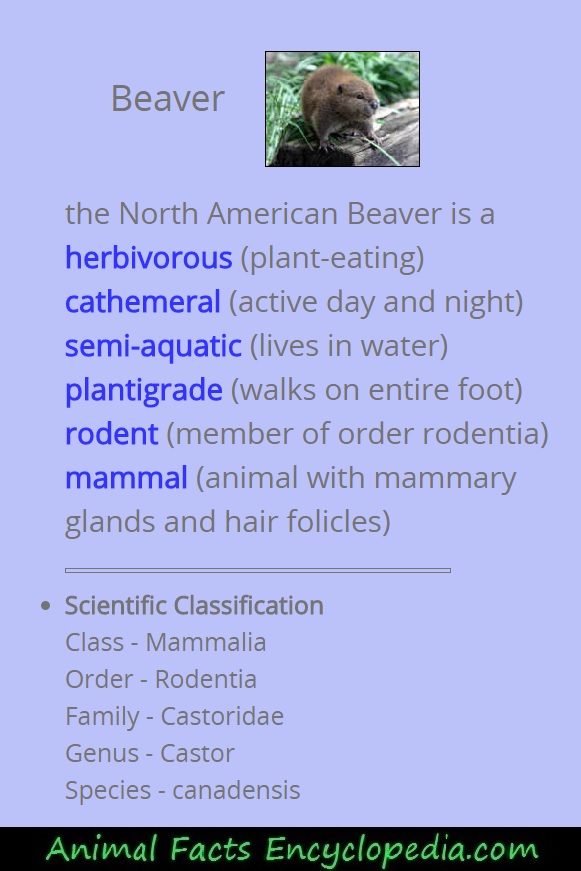

beaver Facts

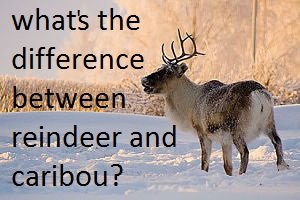

Portrait of a Beaver

Portrait of a BeaverThe social, industrious beaver is a lovely, fascinating animal that has been exploited and misunderstood for centuries. At weights of up to 70 pounds, they are one of the largest rodents in the world, second only to the South American capybara.

And are second only to human beings in their ability to completely alter their environment.

Beavers are round, well-furred animals, with small ears, large, orange-colored front teeth, beady eyes, and webbed hind feet.

Their most distinctive physical feature, though, is a flat, naked, and leathery tail. The tail is shaped like a flounder, and used as a rudder when swimming, a powerful, stabilizing tripod as the beaver sits up on it's haunches, and a storehouse for body fat, which may be necessary in rough winters. But despite the myth, beavers do not use their tails to carry mud, or pack it down.

The beavers incredibly thick, double coat of fur was once extremely popular, particularly in the millinery industry where it was used to make the finest, water-proof top hats for people like Abraham Lincoln. As the Eurasian beaver population was depleted, the demand for beaver pelts spurred on the exploration of Canada, and fed the fur trade between French, English and Native American peoples.

The beaver also has strong, nimble, hand-like front paws, that have semi-opposable little fingers (not thumbs), with which they maneuver all sorts of building materials. And they are remarkable engineers, using twigs, mud, rocks, branches and entire logs to build two different types of structures, dams and lodges.

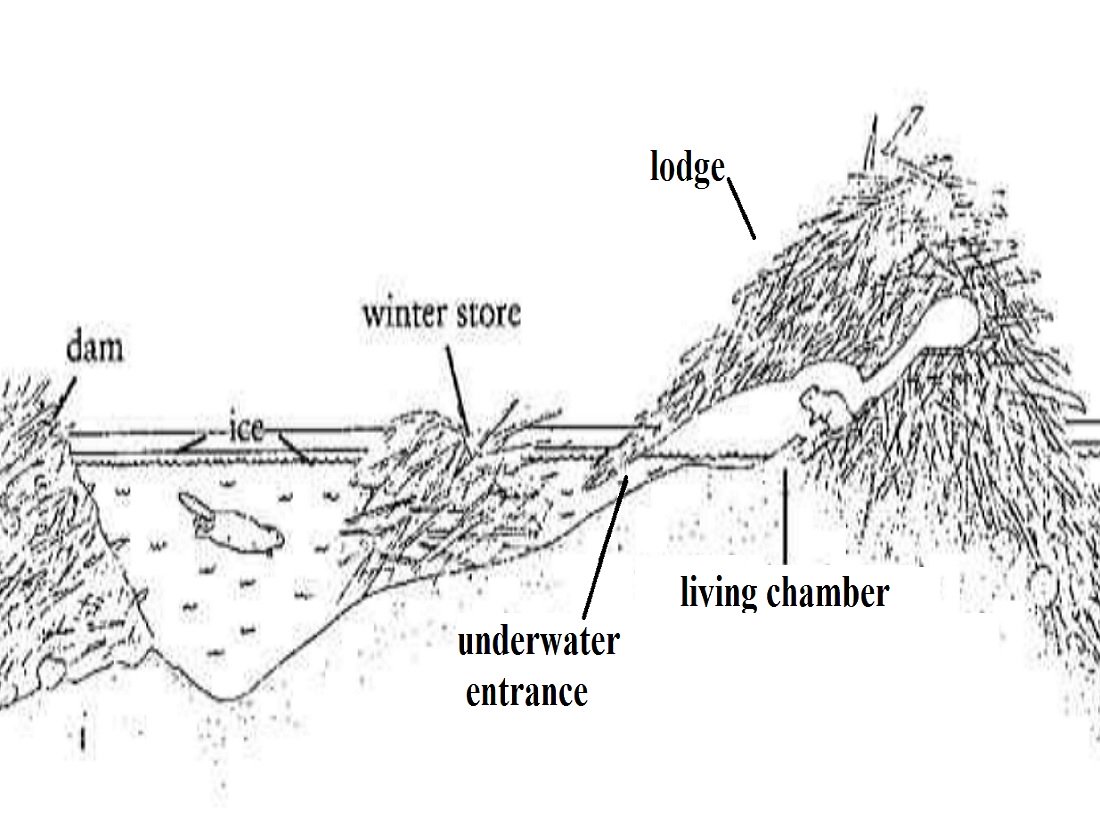

When beavers come into a new location, they first build dams across small streams. The dam traps water behind it and creates a pond. The purpose of the dam is to provide deep enough water for the beaver to build a safe home - called a lodge.

Beavers build their lodge in the middle of the pond, where the pond water provides safety from predators like bears and wolves. But the water level must also be deep enough not to freeze solid in the winter, because beavers live under the ice in the winter, accessing their lodge from underwater entrances and eating twigs and branches they have stored in their submerged larder.

The beaver is a vegetarian who eats not just aquatic plants, but also the twigs, leaves and soft branches of all sorts of trees. They also eat the cambium of the tree, which is the soft, woody layer just beneath the mature bark. Cambium makes up a large part of the beavers diet, and requires that they chew straight through the tough outer bark to get to it.

Beavers don't actually eat the bark, but they can chew through it with ease, using their impressive, self-sharpening incisors. The beavers four front teeth need to be so strong that the enamel on the face of the teeth is infused with iron. The iron rich enamel is resistant to the acidic qualities of tree bark, and causes the teeth to be a bright orange color. The back surface of the teeth are a softer dentin, so the back of the teeth wear out faster than the front, maintaining a tapered cutting edge like a chisel.

There are two species of beaver, the North American beaver, and the Eurasian beaver. They are very similar in appearance with the North American animal being a bit larger, with a rounder head, and a wider tail.

They are both highly social animals that live in small, busy, incredibly cooperative family groups.

Beavers have the longest childhood of any rodent, with youngsters staying with parents for 2 to 3 years as they learn the skills of hydro-engineering. Most active at night, they rely on their excellent senses of smell and hearing, but are extremely near-sighted, and will sometimes simply feel around for things with their little hand-like front paws.

The beaver uses it's front paws in such a human manner, that Native Americans referred to them as "little people", and beavers are, in some ways, quite like us. They constantly manipulate their environment, often for the betterment, but sometimes to the detriment of those around them, they communicate often, with squeaks, whines and moaning sounds, they are affectionate with family members engaging in play and mutual grooming, and they also mate for life.

how do beavers build dams?

Beavers don't live in dams, they build two different types of structures. They create a wide, cone-shaped lodge with underwater entrances to live in, and they build dams to provide them with areas of deep, calm water within which to build their lodge.

Beavers may build several dams along waterways in order to flood a large enough area for a safe home. The lodge requires a water depth of at least 4 feet to prevent freezing of the underwater entrance ways.

Dams average about 15 feet in length and 5 to 8 feet deep, but sizes vary considerably. There is a 2,500 foot long dam in Canada, that was discovered in 2007 when it was seen by satellite. It was constructed over 30 years ago, and is maintained by 14 different beaver colonies.

Beavers start construction of the dam by laying a base of stones or thick tree stumps across the waterway. They can move objects as heavy as themselves, and can fell trees as wide as 24". Once the dam foundation is in place, they begin to place logs and branches across it. They weave these together as they build, and leave lower relief areas along the crest of the dam for water to flow over. Finally, they pack any crevices with mud, pebbles, and moss, to make the dam even more watertight.

If the initial dam does not create a deep enough pond to make a lodge, the beaver may build numerous secondary dams to stop more water flow.

Once the pond is deep enough, lodge construction begins. Beavers create an island of mud in the middle of the pond by dredging the bottom, and pushing mud into a pile with their front paws. Then they build a house on top of the mud, using logs and branches. They cover the lodge with mud, except for the very top which serves as a ventilation hole. Beavers usually re-mud right before the first frost, so the mud freezes and hardens the roof.

In preparing for winter, the beaver gathers large amounts of fresh branches, and carries them underwater to a larder by the entrance of the lodge. They push the ends of the branches into the mud to keep them in place, and access this food during the winter, when the pond has frozen over.

Even when the ice is hard, and predators can walk on it to get to the lodge, it is too well constructed for them to reach the beavers inside. They may see the steam of the beavers breath rising from the chimney hole the beavers leave in the top of their lodge, and may hear the beavers inside, but many a frustrated wolf or cougar has dug at a beaver lodge with no success.

The beavers will emerge in the spring, when the ice has melted, and their family is usually several members larger than it was when they settled down for the winter.

On rare occasions, beavers get trapped inside their lodge, when the water level is too low, or they may be forced to try to get out when they run out of food in their larder, but usually the busy beavers have prepared more than adequately, and survive another cold winter under the ice, in the warmth of their incredible lodge.

beaver lifestyle

Eurasian beaver

Eurasian beaver

Are beavers busy? Well, yeah. Like most rodents, the beaver is a fairly active animal with a relatively high metabolism, but the beaver has allot to show for all the activity.

The North American beaver can be found throughout much of the continent, in areas where there are streams and rivers. They require areas wooded with some younger growth deciduous trees such as Aspen, cottonwood and willow, which they use both as a food source and as building material.

A group of beavers is called a family or lodge, but most often, a colony. The typical colony has 6 to 12 members, which are generally a mature pair and their last 2 or 3 batches of youngsters. Immature beavers are called kits, and they take awhile to mature, hanging around the lodge with mom and dad for 2 to 3 years, learning how to build a proper home.

Beavers are peaceful animals, and show little, if any, aggression. When wild beavers require human handling, for whatever reason, they rarely attempt to bite, but may whine and squeal in protest. Likewise, the lodge they work so hard to build and maintain, may be used by numerous different animals, including dormice and muskrats. These creatures may even eat from the food stores the beavers procure for themselves. But when new beavers attempt to settle in the pond, the colony will drive them off together.

They will also mark the perimeter of their pond with dirt mounds that they scent mark with their own special odor. Beavers have two castor sacs under their tails from which they secrete castoreum, a goo that actually smells rather good to humans, and is occasionally used as a perfume extract and vanilla food flavoring.

The beaver colony spends much of their time maintaining and repairing both their lodge, and any dams they have built, and collecting and storing food for the winter. Edible branches are stored in an underwater pantry called a larder, which they will access from the lodge, when the pond has frozen over. The family may even have a less elaborate summertime lodge that they use until it is time to commit to the winter lodge. And entire colonies may relocate to an entirely new region, if or when resources are scarce.

Youngsters will travel about the pond with their parents getting lessons on tree-felling and roof repair. Parents may use their big flat tails to slap the water as a warning of approaching danger, and the entire colony will dive for cover.

In the water, the beaver is supremely adapted. Their large hind feet are completely webbed between the toes, the tail can be used for both propulsion and steering, the nose and ears clamp closed with special valves when they submerge, and they can hold their breath for about 15 minutes underwater.

On land, however, the beaver is a bit awkward, short-legged and round, with a slow, rocking gait and poor eyesight. Even 60 pound adults can be quick victims when on land, so they prefer not to travel too far on logging trips. When trees and other resources are too far away, they solve the problem by digging canals sometimes hundreds of feet long. These canals, created by simply shoving mud out of the way, are often dug deep enough for the beaver to float log sections down. -Amazing!

beaver!

beaver!beaver reproduction

beaver family

beaver familyBeavers pair up for life, and the female generally comes into season once a year, in late winter. Their yearly courtship involves happy wrestling and play, and mating takes place inside the lodge, at the coldest time of year.

Mother beavers have 3 to 5 babies on average, and the youngsters are called kits. Gestation is about 105 days, and in the last week or so, the mother prepares a soft nest in a nursery chamber of the lodge, which is usually higher up than the main living chamber, and further from the entrances.

The mother gives birth in early spring, when the ice has melted, and the other family members can bring fresh food for her. Newborn beavers are relatively large and well developed. They weigh about 14 ounces, and are already covered with waterproof fur. The eyes and ears are open, and the sense of smell is strong from the moment they're born. Kits begin to chew on fresh vegetation at only a few days old, and are weaned at 2 or 3 weeks. Baby beavers are able to swim within half an hour of birth, but they don't usually venture out of the lodge until they are 3 or 4 weeks old. They will follow closely behind their mother, not in single file as many baby animals do, but in a little half-moon pattern around her rear. When they get tired, they will actually climb up and ride on her back.

Father beavers are exceptional parents and will begin to take the kits on excursions once they have been out a few times.

The other family members, are usually yearlings or teenagers from the last 2 years litters. They also help with the rearing of the babies, swimming with them and babysitting.

Unlike many rodents which are moved out of the house and completely independent in a matter of weeks, a juvenile beaver has an engineering degree to study for.

They begin to train in what is practically an apprenticeship. Watching at first as their parents demonstrate tree chopping, stone positioning, twig arrangement, and waterproofing, and then diving in to help with these various chores. Yearlings begin to work on their own, particularly with the less demanding job of waterproofing the roof of the lodge, or plugging holes in the dam, dredging up armfuls of mud and moss, and pushing it into crevices with their nimble paws.

Eventually, at 2 or sometimes 3 years old, young beavers leave the family pond, usually one at a time, upstream, downstream, or boldly across the valley.

This is undoubtedly the most dangerous time in a beavers life. Without the safety net of family, the security of a familiar landscape, even the comfort of the lodge to sleep in, they may travel for days, and as far as 40 miles to find their own piece of land.

Along the way, other beaver colonies will chase them off, or they may be lucky enough to run into another wanderer of the opposite sex.

Whether alone or in a new relationship, the young beaver will find a new, untouched stream, or perhaps an old dam and lodge, abandoned years before when the large trees ran out, that has regrown, and is perfect for a new colony.

Can beavers fight the impact of drought?

Beavers were once one of the most populous animal in the world, but hunting for their fur and castoreum, which became extremely popular in the 1600's, nearly doomed them. By the 1900’s the beaver population in Eurasia had fallen from 100 million to 1000, in North America from 60 million to just a few thousand, and in Germany from several hundred thousand to only 200.

Fortunately, beavers are making a comeback, but across Asia, Europe and North America, many of the areas where beavers used to be plentiful are suffering from drought. Drought is a period of low precipitation - a basic lack of rain. Beavers can't make it rain, but they can help to keep groundwater and surface water from disappearing during these times.

Naturally, a beaver dam forms ponds and creates aquatic ecosystems that can greatly benefit the environment. A successful family of beavers will spread out and create lush meadows that serve as havens and permanent residences for dozens of species in the wild. But what they create below the waters surface is even more critical.

When beavers build dams, they create a storage mechanism for water, but more importantly, a deep storage mechanism. Beavers dig furrows and dredge deep down into the bottoms of the ponds they form in an effort to make their lodge as safe as possible. Surrounding their lodge with deep water serves two purposes.

First, the deeper water is below the frost line and doesn't freeze, allowing them continued access to the pond, even though it may be sealed over with ice in the dead of winter.

Second, cougars, wolves and bears may be able to catch prey in very shallow water, in fact, bears hunt in water all the time, but they can't catch anything if the water is too deep to stand up in. So, beavers dig deep moats around the lodge, that trap enormous amounts of water, protecting it from evaporation in dry seasons.

Several thousand years ago, the American west was home to giant beavers the size of grizzly bears, and it's landscape was shaped and formed by their activity. Only 500 years ago, the modern beaver was everywhere, and the world's wild spaces looked very different then they do now. But they were hunted for their fur, and eradicated as pests. The beaver is extinct in the wild in several country that it helped to form, like England and

Some activists and researchers are hoping to reintroduce beavers to areas that need them most, and projects are afoot throughout North America to do just that. But organizations like the California Department of Fish and Wildlife actually classifies beavers as a "nuisance" species, and there are many folks opposed to this idea. So can the beaver save the world? We think maybe yes...but they will certainly need our help to do it, and only time will tell...

a few more beaver facts

- Beavers were declared to be fish by the Church, so practicing Catholics could eat their tails for Lent

- Beavers produce a secretion called "castoreum" that has a pleasant taste and is occasionally used as vanilla flavoring

- A beaver can hold it's breath for 15 minutes

- Giant ancient beavers were as big as grizzly bears

- Beavers build dams to create ponds, and lodges to live in

- The beavers incisors are 2 inches long and bright orange

- The beaver is the second largest rodent, the capybara is first

- Beavers may someday help us survive drought

Scientific Classification:

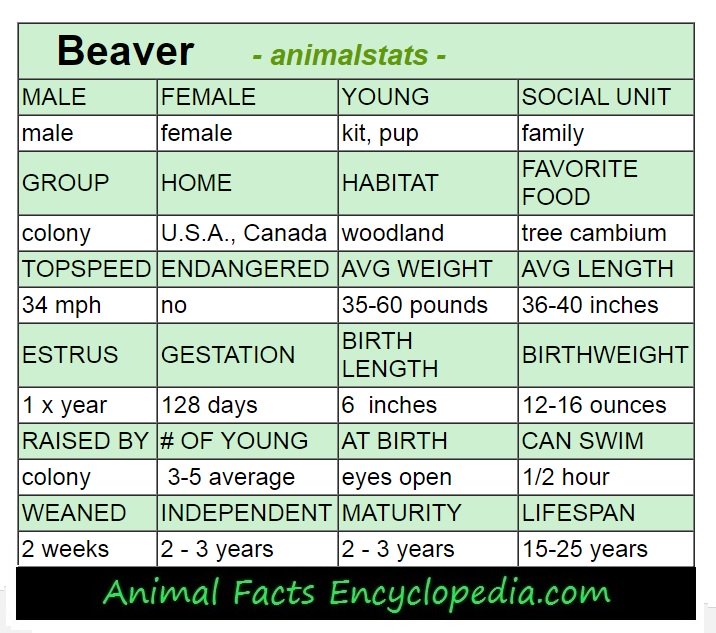

| Beaver - animalstats - | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MALE | FEMALE | YOUNG | SOCIAL UNIT |

| male | female | kit, pup | family |

| GROUP | HOME | HABITAT | FAVORITE FOOD |

| colony | U.S.A., Canada | woodland | tree cambium |

| TOPSPEED | ENDANGERED | AVG WEIGHT | AVG LENGTH |

| 34 mph | no | 35-60 pounds | 36-40 inches |

| ESTRUS | GESTATION | BIRTH LENGTH | BIRTHWEIGHT |

| 1 x year | 128 days | 6 inches | 12-16 ounces |

| RAISED BY | # OF YOUNG | AT BIRTH | CAN SWIM |

| colony | 3-5 average | eyes open | 1/2 hour |

| WEANED | INDEPENDENT | MATURITY | LIFESPAN |

| 2 weeks | 2 - 3 years | 2 - 3 years | 15-25 years |

see more animal extreme closeups

Recent Articles

-

African Animals - Animal Facts Encyclopedia

Oct 11, 16 10:27 PM

African Animals facts photos and videos..Africa is a wonderland for animal lovers, and a schoolroom for anyone who wants to learn about nature, beauty and the rhythm of life -

Baboon Facts - Animal Facts Encyclopedia

Oct 11, 16 10:26 PM

Baboon facts, photos, videos and information - Baboons are very distinctive looking monkeys with long, dog-like snouts and close set eyes. -

Great Apes Facts - Animal Facts Encyclopedia

Oct 11, 16 10:25 PM

Great apes facts, photos and videos..Human beings did not evolve from chimpanzees, modern chimps and gorillas do not appear in the fossil records until much more recently than homo sapiens..