All about dogs

Portrait of a Dog

Portrait of a DogOur magnificent partner in crime, the domestic dog, has been living and bonding with human beings for 12,000 years or more. Although they work beside, and for us as well, their value to us as enriching companions has allowed them to flourish, and caused modern humans to devote extraordinary resources to their well-being.

Once considered to be a subspecies of grey wolf, recent DNA research shows that dogs and wolves have been evolving separately for more than 30,000 years, and that the last common ancestor, a small (perhaps 40 pounds) Eurasian wolf, is now extinct.

All dogs, including wild dog species like the dingo, are more closely related to extinct wolves, than they are to any living wolf species.

So with these time frames in mind, it appears the dog was already a dog, and not a wolf, when the process of domestication took form. But the lifestyle of the wolf is what made them so amenable to domestication, and the type of dog that first warmed itself by a human's fire, was used to the teamwork and closeness of pack life, making it eager for social structure.

The modern day domestic dog is a wonder of evolution. A passive, natural process shaped the psyche of early dogs, where those that were friendly and helpful, were provided food, shelter or protection.

But over the last few hundred years, like a bit of a Dr Frankenstein, the human being has manipulated the structure of it's willing companion into an awesome array of styles, colors, hairdos and personalities.

Dogs have the largest range of size of any species of animal, from 2 pound Chihuahuas to 220 pound Mastiffs that stand between 6 and 42 inches at the shoulder. Horses do have similar extremes of height, but they have nowhere near the diversity in skeletal variation.

The skull shapes present in the domestic dog are nearly as varied as the skulls that occur within the entire family of carnivores.

There are critical differences, from breed to breed, in craniofacial angle, which is the angle between the forehead and the jawline, the mandible construction and how the jaw is joined to the skull, shape and position of eye sockets (orbits), and the angle and structure of the junction between the skull and the neck.

All of these aspects of skull morphology are specific points that biologists and archaeologists used to identify unique species of animals, just from their skeletons.

Looking at an assortment of modern day dog skulls, a scientist would conclude that they are handling the bones of vastly different species, even a different genus, family, or order of animal.

Sharpei, Doberman, Chow chow, Chihuahua, Borzoi, and Neapolitan Mastiff - dogs!

Sharpei, Doberman, Chow chow, Chihuahua, Borzoi, and Neapolitan Mastiff - dogs!But these are all dogs, all the same species, all able to interbreed (with a little help sometimes) and produce fertile young. For the casual observer, the length of the snout is the most obvious variable. Short-nosed dogs are call brachycephalic breeds, and long-nosed dogs are called dolichocephalic breeds.

Even something as simple as the ear, which is virtually unchanged across approximately 350 breeds of modern horse, in the dog, has over a dozen specific variations.

There are well over 300 different breeds of domestic dog worldwide. A breed being a variety of animal so true to type that the offspring of purebred parent animals will invariably mature to a very predictable size, structure and temperament.

Many of these breeds developed naturally, as the amiable dog cast it's lot with the adventurous human, and found itself all over the globe. Spitz type dogs with thick winter coats and bushy tails developed in cold climates, lean, thin-skinned bodies were more successful in the deserts.

Dogs who differed based on what their humans hunted, sprang up in all corners. Small, fearless terriers who "took to the earth" following vermin right down in the burrow, and broad-jawed, boulder-shaped animals who could latch onto a bull.

But the hunting instincts that may have been key in the initial partnership, were not just modified by humans, they were twisted and tweezed to create the dutiful shepherding breeds and the tireless, docile retrievers. Carnivorous, fang-toothed creatures who, to please us, track and control lambs but don't kill, take fresh kills in their mouths but don't eat - Amazing!

Then think of the value of dog as companion, and witness the result of it's unsurpassed skill in this role. Dozens of specifically shaped and colored breeds, different sizes, different coats, head shapes, muzzle lengths, eye sets, tail configurations, curated for one purpose - to share our lives, to give us joy, to improve our existence, with their existence.

Witness the Lhasa Apso, a truly ancient breed dating back to 800 B.C., and one of only a few modern breeds most closely related through DNA testing to the original ancestral wolf, from which all dogs can be traced.

Although they may also have been used as sentinel dogs, kept in the courtyards of homes to alert the occupants of visitors, the emphasis on small size, and a luxurious coat means that breeding dogs specifically for companionship either coincided or proceeded breeding for a work-related porpose such as herding or hunting.

There is nothing else like it in the animal kingdom - the versatile, brilliant, empathetic, humorous and humble dog.

man's best friend

Millions of years ago, the earliest ancestors of all canids developed in North America, while the earliest ancestors of human beings developed in Africa. But ancient wolves and ancient humans didn't meet until groups of both migrated to Europe and Asia.

While fossilized records of homo sapiens date back about 200,000 years, fossils that are clearly identified as dogs are only about 15,000 years old. So it is suspected, but not proven, that the wolf ancestor of the dog was the first to begin living with humans, and then evolved into the dog, but it is possible that the animals that were first tamed, were more dog than wolf.

Many of these questions are up for debate, but there is no doubt that a long time ago, a now extinct wolf-type or dog-like species, and nomadic human beings, began to form a unique alliance. It is the parallel social structure of both humans and wolves that made the union not only possible, but very successful.

When we study modern wolves we see some of the most gregarious, bonded creatures on Earth, with an incredible drive to cooperate and conform to the social structure. Pack life, with a clear order of dominance, and a powerful sense of community, including communal hunting and sharing of resources, the defending of common territory, and the cooperative raising of young, is a hallmark of both humans and wolves.

These animals that hung around the fire, and kept the campsite clean of scraps, used body language, vocalizations, facial expressions and eye contact to communicate, just like us. They may have been outcasts or orphans at first, who clearly indicated submission, were extremely curious about human activity, and needed the safety of a pack to survive.

They had ingrained and instinctual desire to track and flush game in a group, and concede the kill to dominant members of the pack before they ate their share, so hunting together may have been the first shared experience.

The first overtures were probably made by them, but once human beings realized they could utilize these animals for all sorts of things, the process of domestication was probably rather swift. Some estimate that it may only have taken a few decades to see noticeable physical and psychological changes, culminating in a whole new animal - the domestic dog.

In fact, an experiment that took place in Russia in the 1960's, and still lingers today despite a lack of funding, found that foxes selectively bred for "tameness", not only lost their fear of humans and began to desire human contact, but also changed in appearance, most notably developing coats with white patches, and curly tails, in as few as a six generations.

So at some point, as two species evolved together, they began to view eachother as social partners, enjoying the company of the other, developing a mutual language of play and affection - but also of problem solving.

In a telling Hungarian study, wolves that were raised by humans and completely tame, socialized and kept as pets, were pitted against identically raised dogs in a simple experiment. Food was placed in view, but in an inaccessible area.

Both wolves and dogs attempted to get at the food themselves, but after only a minute or two of failure, the dogs looked to the experimenter for help. The wolves simply continued to try to access the food themselves, for minutes at a time, without ever turning to their caretakers for help.

Not only did the dogs look for help, after a few minutes of frustration, most of the dogs turned their attention almost completely toward the experimenter, making strong eye contact, and imploring them to access the food for them. This ability to shift attention from the resource to a human being, was clearly instinctual in the dogs, not the wolves.

The idea of a dog viewing us as the means to an end, a resource, or even a tool, isn't news to anyone who has ever owned a dog, but understanding how their relationship with us has changed through the domestic experience, is pretty cool.

A bit more on dog intelligence here: Pigs are not Smarter than Dogs

so do dogs love us?

There is a common myth that dogs don't like to make eye contact, or that looking directly at your dog is a threat.

Well, just like staring in human society, eye contact between dogs and humans comes in many forms, and is interpreted simultaneously with the accompanying facial expression, body language, common knowledge and situation.

A stern, unbroken stare can, in fact, be a threat, or a show of dominance, but dogs and humans are also guilty of "staring into eachothers eyes" and it is anything but unpleasant.

We know that human beings get a rush of the hormone, ocytocin - otherwise known as the "love hormone", when we look at our children, romantic partners, and yes, our pets.

The coolest part is that recent experiments show dogs get the same rush when they look at their owners - some pet cats produce the hormone when looking at their owners too, but not consistently, and at nowhere near the levels of our canine companions.

In fact the rush of ocytocin that pet dogs experience when they look into their owners eyes is the same level that humans experience during the first few months of "falling in love", but unlike with human beings, your dog never falls out of love with you, the honeymoon is never over, and they will never get the "seven year itch."

And that's why they wiggle when you come home.

dog lifestyle

Most modern dogs have not practiced the trade for which they were developed for generations. Chances are, though your beagle was built with droopy ears, a masterful nose, and a rollicking voice, he's never been on a fox hunt. Your Siberian husky has never pulled a sled, and your wolfhound has never seen Russia, or a wolf.

But the natural inclinations that made them a good choice for a particular job, and the, in some instances, thousands of years of selective breeding to ingrain certain tendencies, and sculpt the correct form, still have influence over their behavior.

Understanding what your dog was originally bred for, can help you choose the best dog for you, or at least help you to accept what you can't change about the dog you already have.

Breeds exist because dogs were specially selected and designed for different jobs, so, generally speaking, a breeds original purpose - even if it was thousands of years ago - can have allot to do with the present day dogs behavior.

For example, some dogs that have the most difficulty adapting to life as house pets, were originally used as what were called "sentinel dogs". They were stationed, usually alone, in a courtyard, or foyer, to guard against intruders. Breeds like the Akita, the Shar pei, the Chow and the Tibetan mastiff, represent modern versions of these dogs, and because they originally guarded an area that they considered their own, and usually worked alone, an aggressive, independent personality was required. Problems with discipline and aggression are not uncommon with any breed that had a history as a sentinel dog, and their original purpose is the fundamental reason.

Dogs like Malamutes, Dalmatians and Siberian huskies were bred to run long distances. They sometimes have hyper-activity problems and trouble settling down in a house, and may do what they were designed to do - run- when they get the chance. These breeds are notorious for being found sometimes hundreds of miles away from their homes if they should get loose, and shelters often have difficulty finding the original owner.

All terrier breeds were originally bred to hunt and kill mice, rats and even rather fearsome animals like badgers and raccoons. They may be aggressive with cats and other small animals in the house, may be pugnacious with other dogs, may have a tendency to dig in the yard, and, because they also usually worked independently of humans, may challenge your authority.

Any dog that was specifically bred to fight other dogs, was subjected to perhaps hundreds of years of breeding that specifically encouraged aggression towards their own kind. Breeders of fighting dogs broke down the pack mentality and kept dogs separated by chaining them just out of reach of eachother and encouraging competition for food and other resources.

The descendants of dogs that were successful in this field, may still have problems with socialization because of this. The most disturbing manifestation of dog-fighting, is that because they were trained to fight other predators, immobilizing the head was a priority in dogfights, so these dogs tend to go for the head or face when in any kind of confrontation.

Dogs like retrievers have worked very closely, side by side with human beings as they were shaped into hunting partners. They learned not only to take direction from humans in the form of hand signals, whistles and words to find game, but were also bred to pick up birds as fragile as doves, and return them to their masters without harming a feather.

They are exquisitely fine tuned to understand our desires, and have parlayed the hunting skills born in them, into the tools that make them the outstanding service dogs, devoted seeing-eye dogs and amazing pets that they are today.

Finally, many toy breeds, like the Italian Greyhound and the Havanese, were not bred with a specific job in mind, other than the "job" of companionship. "Lapdogs" may be the most uniquely qualified pets, and tend to be very in tune with their owners emotions.

Trends and fads can also influence the personality of a particular dog. Breeding for size - large or small - head shape, coat type, or color without regard for personality or health can lead to problems within just a few generations. And something as silly as a breeds popularity spiking due to a character in a movie, can cause breeders to abandon ethics, breed and sell as many puppies as they can during the hot streak, and leave the breed with serious personality flaws or physical issues.

So while knowing the history of a pure breed dog can give you insight into it's "pet potential", your gut instinct when you look into the eyes of that pound puppy, may be the best barometer of all!

beagles!

beagles!dog reproduction

The female dog comes into season twice a year. The process is commonly called "heat", and the entire cycle lasts 2 to 3 weeks. The female's genital area will swell, she will have a bloody discharge and she will urinate more frequently. The urine contains pheromones and hormones the scent of which attracts male dogs.

Females in heat may be restless, may show "nesting" behavior, and may try to escape. Nearby dogs may also attempt to escape and find the female, and sometimes local males may be agitated and aggressive with eachother if a female in heat is in the neighborhood.

One curious point about certain dog breeds is that they have been bred to a point of such extreme anatomy that natural copulation, and/or natural birth is actually physically impossible. For instance, do to their bulbous torsos and weak hips, most male French bulldogs are actually incapable of successfully mounting a female, and the majority of these dogs are conceived through artificial insemination.

Likewise, Boston terriers, Bulldogs and a host of other broad-headed breeds are regularly delivered through cesarean section, since the mother's hips are often too narrow to pass the big-headed babies.

In addition, the females of many tea-cup type breeds are often too small to risk pregnancy at all, and larger females are usually used in matings with the smallest males to maintain the tiny size.

The smallest toy breeds also tend to have the smallest litters, often just 1 or 2 pups at a time, while some very large breeds like the Saint Bernard and the Newfoundland have astonishing numbers of puppies - 12, 13, sometimes more!

The largest litter on record is said to be 24 puppies in 2004 by a Neapolitan mastiff named Tia.

She is pregnant for 58 to 68 days and usually gives birth to an overall average of 5 puppies, varying a bunch by breed.

Newborn puppies are born in a translucent placental membrane sac that the mother quickly licks away. The newborn has eyes and ears shut, but it's sense of smell kicks in quickly, and it's nostrils begin to move within moments of birth, sniffing in the new world.

Puppies have fine, silky hair, and can be very vocal right away. Some breeds are born with all their adult markings in place, while others, like Dalmatians and English setters are born without markings, and develop spots as they grow.

Males don't usually have much to do with raising the puppies, but with most domestic dogs, the mother gets allot of help from her human family.

Domestic mother dogs are naturally less vigilant and protective of their pups, as the humans they live with are all considered pack members, and most domestic puppies don't need to worry about predators snapping them up.

Puppies are weaned at 6 to 8 weeks of age, and are often sent off to new homes at this time.

Female pups may have their first heat as early as 4 months, but 8 to 12 months is more common. Small dogs are full grown within the first year, but some giant breeds may take 3 years to reach full size.

Check Out Our Puppies Page!

the mind of the dog

Although great apes and whales have huge complicated brains, they haven't evolved with us as dogs have, and don't understand forms of communication that we use with dogs and take for granted.

Although they don't have arms and fingers, and must be taught to point at things with their noses, most dogs instinctually understand and respond accurately to the human pointing gesture, without any special training.

This is a skill that is most precise in hunting and herding dogs, but the majority of dogs, even puppies as young as six weeks, understood the significance of the human hand pointing to an object.

Wolves raised by humans don't have the skill, and only 1 out of every 200 or so domestic cats seemed to respond to human pointing.

Dogs will also respond to a human being simply looking at an item. They will follow the gaze of their owner, and also understand that we can't see them when we are in another room, or even when our eyes are closed.

Experiments prove that some dogs instructed to leave things alone, disobeyed when the experimenter was out of sight, or even when the experimenter closed their eyes.

In short, dogs have a tremendous, instinctual understanding of human gestures, and the human face. They are born knowing us.

Herding dogs learn to move herds of sheep across acres of land by listening to commands whistled to them from, sometimes miles away across hilltops. These dogs know about a dozen special whistle commands that include the difference between right and left, sometimes require them to drive the herd away from the handler, which can be tough to teach, and may also require them to leave the herd and go back and look for a lost lamb, all on their own.

Dogs trained to guide the blind, must use their ability to generalize as they apply the skills they learned - for instance, safely crossing an intersection- to hundreds of different intersections during the course of their very productive lives.

Seeing-eye dogs also have to learn to look up, for obstacles that might impact their human, and in doing so must understand the concept of scale, the art of anticipation, and the ability to solve the problem by re-charting a safe course, and they may accomplish all of this in the middle of a bustling street, with hundreds of distracting sights, sounds and smells.

Dogs trained in police work, must track and take down people who may be hostile to them, and who may strike and even shoot them. They must control their prisoner while causing a minimum of damage, and release them the moment they are instructed to.

Dogs are also trained to use their sense of smell to track lost travelers, find contraband, and even detect cancer, diabetes and seizures - Amazing!

a few more dog facts

- Dogs have been domesticated longer than any other animal

- There are over 300 breeds of dogs worldwide

- Some dogs can recognize over 1000 words

- There are approximately 600 million dogs in the world

- Dogs range in size from 2 to over 200 pounds

- A dogs sense of smell is 10,000 times more powerful than ours

- Bloodhounds don't smell blood, the "blood" in their name refers to bluebloods - because at one time only royalty could own them

- Yorkshire terriers were bred small so they could hunt rats and mice in factories where they fit under the machinery

- The Russian wolfhound - or Borzoi- really did hunt wolves, but they hunted in groups of four or five

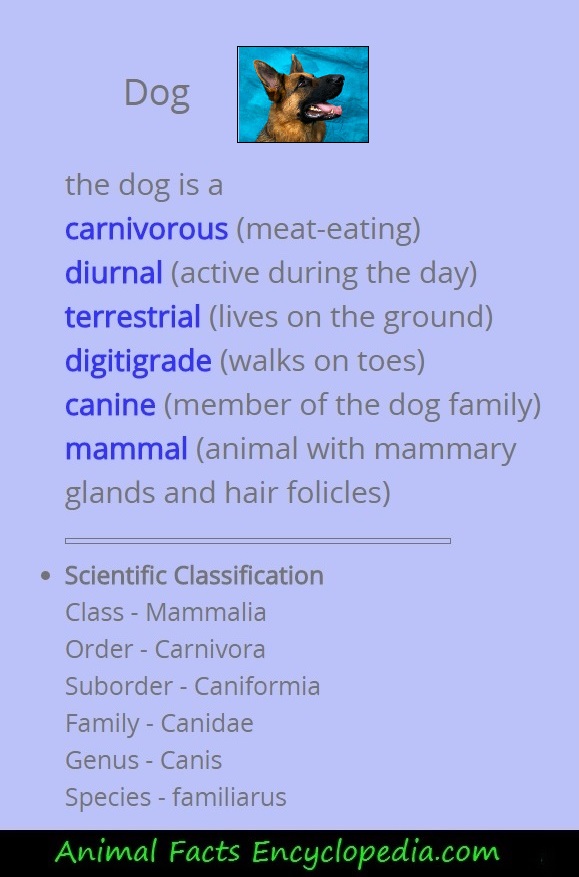

Scientific Classification:

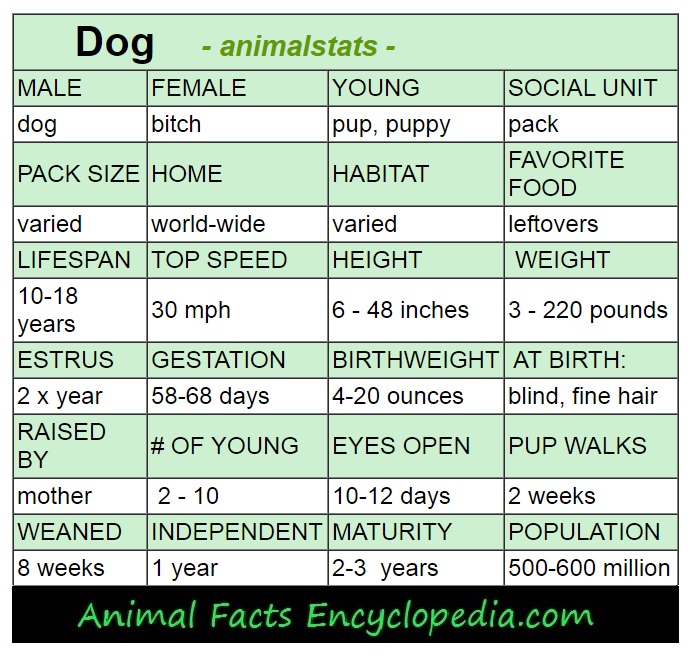

| Dog - animalstats - | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MALE | FEMALE | YOUNG | SOCIAL UNIT |

| dog | bitch | pup, puppy | pack |

| PACK SIZE | HOME | HABITAT | FAVORITE FOOD |

| varied | world-wide | varied | leftovers |

| LIFESPAN | TOP SPEED | HEIGHT | WEIGHT |

| 10-18 years | 30 mph | 6 - 48 inches | 3 - 220 pounds |

| ESTRUS | GESTATION | BIRTHWEIGHT | AT BIRTH: |

| 2 x year | 58-68 days | 4-20 ounces | blind, fine hair |

| RAISED BY | # OF YOUNG | EYES OPEN | PUP WALKS |

| mother | 2 - 10 | 10-12 days | 2 weeks |

| WEANED | INDEPENDENT | MATURITY | POPULATION |

| 8 weeks | 1 year | 2-3 years | 500-600 million |

see more animal extreme closeups

Recent Articles

-

African Animals - Animal Facts Encyclopedia

Oct 11, 16 10:27 PM

African Animals facts photos and videos..Africa is a wonderland for animal lovers, and a schoolroom for anyone who wants to learn about nature, beauty and the rhythm of life -

Baboon Facts - Animal Facts Encyclopedia

Oct 11, 16 10:26 PM

Baboon facts, photos, videos and information - Baboons are very distinctive looking monkeys with long, dog-like snouts and close set eyes. -

Great Apes Facts - Animal Facts Encyclopedia

Oct 11, 16 10:25 PM

Great apes facts, photos and videos..Human beings did not evolve from chimpanzees, modern chimps and gorillas do not appear in the fossil records until much more recently than homo sapiens..